Carl Cheng: Nature Never Loses Exhibition

- Editor at Titan Contemporary Publishing

- Dec 26, 2025

- 4 min read

Written by Joas Nebe

Carl Cheng: Nature Never Loses

3 December 2025 - 10 May 2026

Museum Tinguely

Paul Sacher-Anlage 1 4058 Basel Museum: +41 61 681 93 20 Shop: +41 61 688 94 42 Bistro: +41 61 688 94 58

Opening hours

Tuesday to Sunday 11 am to 6 pm Open until 9 pm on Thursdays Monday closed

The Tinguely Museum in Basel is showcasing an exhibition by the American artist Carl Cheng (*1942). This exhibition focuses not only on his works relating to the themes of art chambers and land art but also on his explorations of the medium of photography. Cheng is interested in transitions: the transitions between various life stages of objects, between usable items and those that have lost their meaning and purpose, which become like stones or shells exposed to erosion, and the transitions of photography into other art forms like sculpture, or from sculpture to photography.

“Anthropocene 1” and “Anthropocene 2” (both 2006) initially appear like satellite images of an agrarian landscape. In “Anthropocene 2,” one might distinguish fields where grains are cultivated, forming varying shades of green squares. Other areas ranging from beige to darker brown seem to lie fallow until planting begins again the following year. At the edges of the fields, several silver-colored cylindrical grain silos are visible, alongside barns and administrative buildings. In another part of the image, dark gray apartment blocks appear staggered, with access roads in between. “Anthropocene 1,” on the other hand, seems to be a satellite image of a larger tract of land similar to “Anthropocene 2” divides into individual agricultural regions covering the entire image area. Both works are the size of large panel paintings or photo prints akin to those by Thomas Struth.

Upon closer inspection, the viewer realizes these are not actually photographic captures from a satellite or drone, but rather simulations of such images created using circuit boards. The grain silos are revealed to be capacitors, the green and brown fields resemble circuit board substrate, and the apartment blocks represent components of the board.

The medium of photography today is largely dependent on computer chips. The size of these chips determines the amount of data a camera can provide to the photographer. Behind the chip technology, which has replaced the earlier chemically and physically based processes of image capture onto a photographic medium (the negative), lies the transformation of environmental visual information into data amounts. A modern digital camera is nothing more than a computer for image processing. Cheng draws attention to this connection through his deliberately chosen imagery, the circuit boards that simulate a photograph.

Another example of Cheng’s fascination with perceptual tipping points is found in his photo-sculpture series “Landscape Essay” (1967), “Nowhere Road” (1967), and “Sculpture for Stereo Viewer” (1968). In “Landscape Essay,” a male figure, with his back to us, pushes a wheelchair away from himself. This is a crop from a photograph, encased in a plastic form that gives it a sculptural quality. The back of the male figure bulges toward us at the right angles, so that the light reflections from the lamps mounted above the Plexiglas box mirror on his shoulders and the upper part of his back. The man appears to be bending forward, moving away from us.

A similar effect occurs in “Sculpture for Stereo Viewer.” The title refers to the sculptural quality and the doubling of the figure, which holds a set of inflated balloons above its head. In stereophotography, which emerged at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, viewers look through a box with two lenses at two photographs taken with slightly offset image content to create the impression of three-dimensionality. Cheng, however, omits the viewing box and broadly references historical stereophotography through the duplication of the cut-out figure of the balloon seller. The balloons achieve a three-dimensional effect through a plastic form similar to that of the male figure's back in “Landscape Essay,” illuminated from above to enhance the light-dark contrast of the balloon photograph.

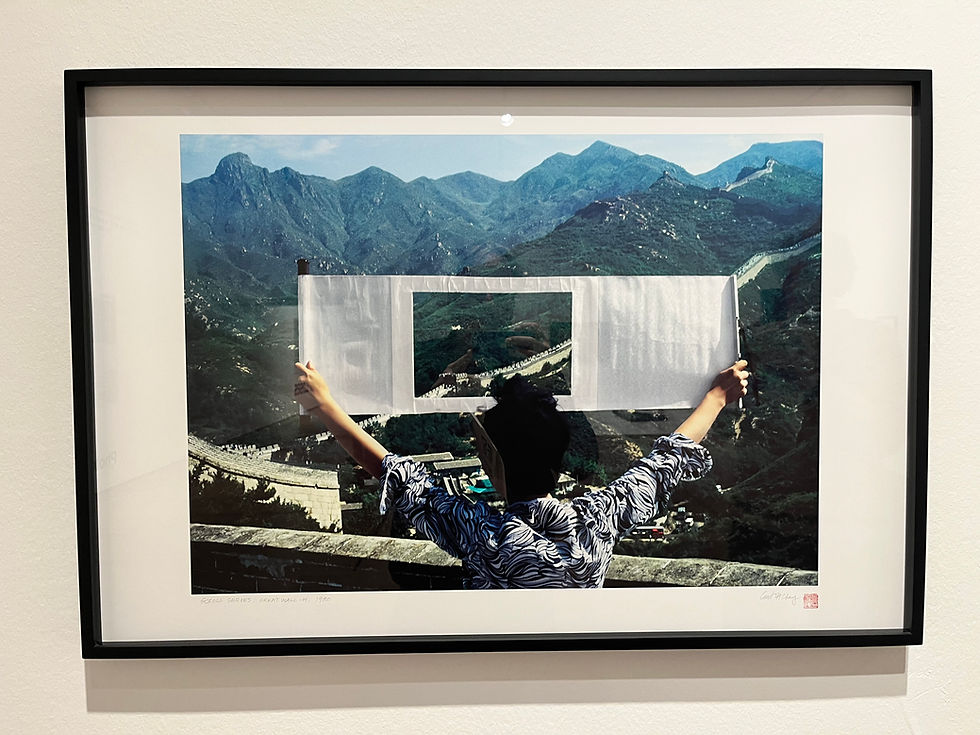

In the “Scroll Series,” Cheng plays with the traditional conventions of roll paintings in Chinese and Japanese scholar paintings. Typically, landscape images in this cultural sphere were painted on paper mounted on bamboo mats, which could be rolled up and stored away, only to be brought out for viewing. As a result, an occasion-specific presentation inherent to the medium of ink painting, in relation to the presentation format of photography from the West. The photographic print is light-sensitive and cannot be continuously displayed without interruption. Likewise, preserved protected from light and generally taken out and shown only for specific occasions. This distinguishes photography from oil painting, for example.

In his “Scroll Series,” Cheng employs a roll format that features a rectangular cutout instead of a traditional ink painting. In “Scroll Series: Bamboo Grove - Horizontal 1” (1979), he stretches the bamboo mat between two bamboo poles, allowing a bamboo branch with leaves to reach through the square opening in the mat into the foreground. Such bamboo branches could indeed serve as motifs in traditional ink painting, but they would end where the paper, mounted on bamboo, concluded. By extending beyond the image edge, Cheng references the boundaries of the genre and such conventions.

In “Scroll Series: Great Wall 1” (1979), a person holds the unrolled bamboo mat between their outstretched arms, and the square cutout reveals a part of the Great Wall of China, a picture within a picture. The transience of the image is emphasized further by the fleeting posture of the person’s outstretched arms holding the image. Eventually, they will have to lower their arms and the bamboo roll, as fatigue sets in. Thus, the chosen cutout is more ephemeral than the selected view of the bamboo branch in the open square of the roll stretched between the bamboo poles.

Cheng's approach to the medium of photography is both playful and experimental, as seen in “Scroll Series” and “Anthropocene.” On the other hand, he pushes photography up to limits by refusing two-dimensionality, dissolving proofs through the addition of a plastic form, or highlighting its transience, as in “Great Wall No. 2.” Even though the works showcased were created over a span of half a century, they remain relevant today through their fundamental inquiry into the medium of photography.

Photo credits: Carl Cheng, Museum Tinguely, Joas Nebe